Inspiration or Imitation?

During my work as a trader in vintage design lighting, I have come across many different lamps. Each one is unique and features its own story; however, occasionally I find two lamps that don’t seem too different from each other. They even look identical at first glance. After taking a closer look and doing research, I often find out that they are actually made in different factories and in different time periods. You could go as far as calling them brothers from another mother. In this article, I will dive into a few examples and differentiate between coincidence, imitation and inspiration. In relation thereto, I will try to find out why manufacturers didn’t always make something truly original.

Examples

1.

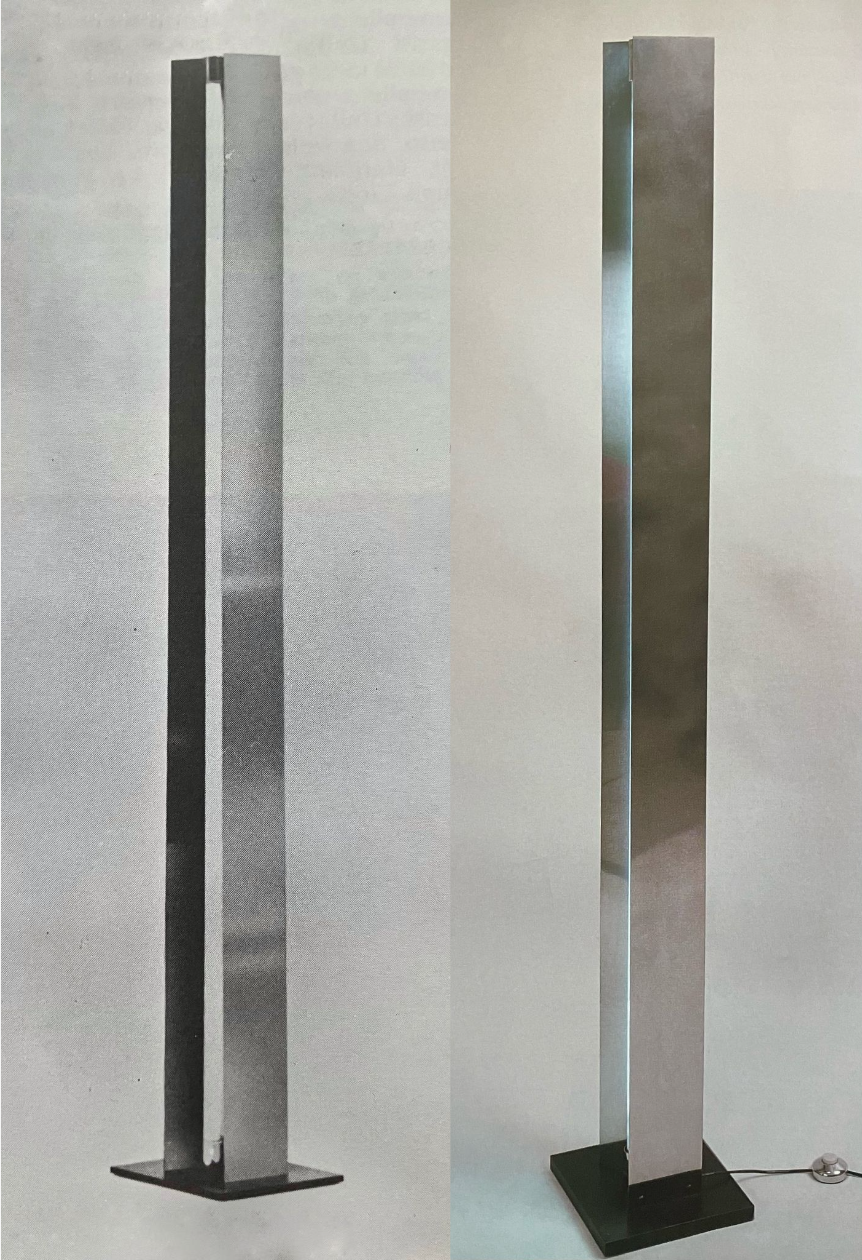

A. Moonlight floor lamp by Ettore Sottsass for Arredoluce

B. Art. 225/1 by Bosi, Martini and Bertotti for Fratelli Martini

(1) A. Moonlight floor lamp by Ettore Sottsass

(2) B. Art. 225/1 floor lamp by Flli. Martini

These two floor lamps, which look the same, are very different if you take a closer look. Italian designer Ettore Sottsass, known for his work at, among others, Memphis Milano and Stilnovo, designed a floor lamp called the Moonlight for Arredoluce in circa 1972–73. It was a very modern design for that time, featuring a stainless steel structure that holds a fluorescent light and is surrounded by a blue-colored plastic-like material.

This style is called the New Italian Design, which began in 1968–1973. During this period, many new Italian lighting manufacturers were established. They often created radical designs that were very futuristic and modern. Traditional materials such as brass and glass were replaced by plastic. It was a “new” material that was very suitable for creating unusual shapes and structures. Designs that were previously impossible to make could now be realized with this new material. The possibilities were endless. Designers were no longer limited in their thinking. Many lamps created in this period are avant-garde in design.

As a counterpart we have a lamp designed by a rather small and unknown lighting manufacturer from Modena, Italy, named Fratelli Martini (The Martini Brothers). They created a lamp that is almost indistinguishable to the Moonlight lamp by Sottsass. This floor lamp was presented as Art. 225/1, designed by Bosi, Martini, and Bertotti. The shape of the lamp is the same as Sottsass’ design and it also holds a fluorescent light, but unlike the Moonlight lamp it is fully adjustable and was produced in several colors: silver (steel), white, red, and blue. Four adjustable shades that surround the lamp are used to “fold in” the light. This kind of lighting design was unique and unlike anything else ever made before. The lamp was presumably designed in 1974–75. Several advertisements for this lamp appeared in editions of the lighting magazine Formaluce in 1975. We don’t know if the Moonlight lamp was a source of inspiration for the Martini Brothers; this could very well have been the case. But up until this day, the lamp created by Martini has often been wrongly attributed to Ettore Sottsass in ignorance. An original Moonlight floor lamp is rarely offered on the internet and is incredibly hard to find.

2.

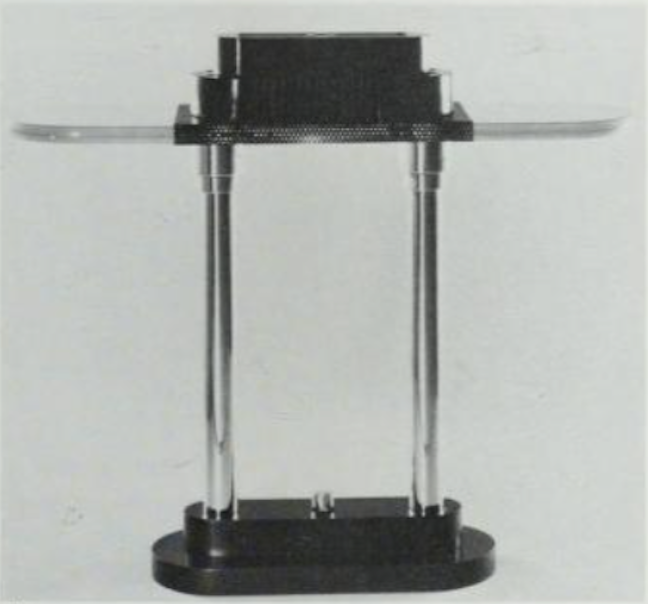

A. Pausania desk lamp by Ettore Sottsass for Artemide, 1982

B. 6770 desk lamp by Robert Sonneman for George Kovacs

(3) A. Pausania desk lamp by Ettore Sottsass

(4) B. 6770 desk lamp by Robert Sonneman

Next we have a design with multiple versions. The first was presumably the Pausania desk lamp, designed by Ettore Sottsass for Artemide in 1982. It’s a rectangular desk lamp, which can be recognized by a base holding two double rods and the green “roof” of the lamp that shines light onto the surface. This kind of design can be called a banker’s lamp, which refers to the authentic desk lamps from the early 20th century. These lamps often had a green shade of metal or glass.

A lamp that strongly resembles the Pausania desk lamp is the model 6770 desk lamp, designed by Robert Sonneman for George Kovacs (United States). The shape is the same, but the two rods are closer together, and the roof is partially made of glass. It is unclear when this lamp was designed exactly, but I presume between 1985 and 1990. In later years, many manufacturers, among others Chinese fabricators, started copying the design by Sonneman and making their own versions.

These two lamps are undoubtedly very similar in design. Do you think the Pausania desk lamp by Ettore Sotsass was inspirational for Robbert Sonneman?

3.

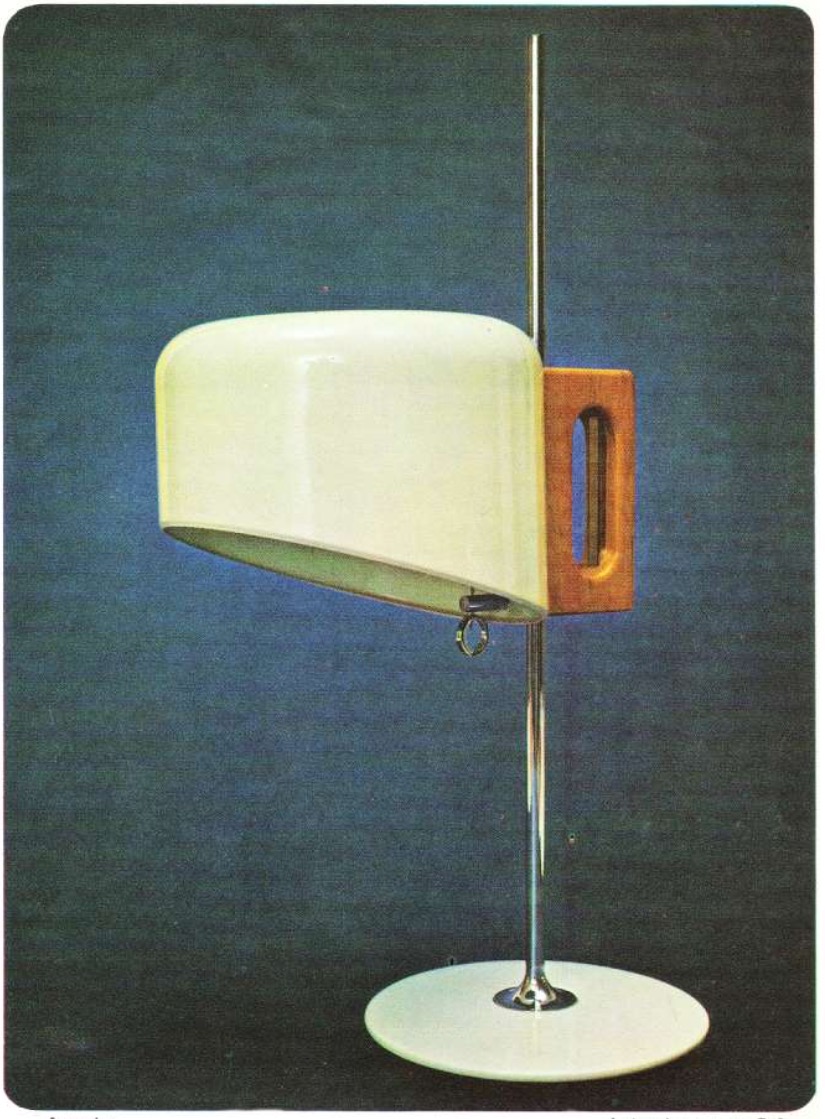

A. Coupe desk lamp by Joe Colombo for Oluce, 1967

B. Apolo desk lamp by Fase Madrid

(5) A. Coupe desk lamp by Joe Colombo

(6) B. Apolo desk lamp by Fase Madrid

This example features two of the most obviously comparable lighting designs. The Model Coupe series from 1967, produced as floor, wall, and table lamps, was the successor of the Spider series, which won the Italian design award Compasso d’Oro in 1965. Both series were created by the well-known Italian designer Joe Colombo for the Italian lighting manufacturer Oluce. The Coupe was a very successful design, one that could be called an Italian classic in vintage design lighting. The Coupe and Spider series are still being produced today.

This huge success was also noticed in Spain, by the manufacturer Fase to be precise. Fase was a well-respected and successful lighting manufacturer from Madrid that was established in 1964. They were known for their highly modern and distinctive desk lamps which they exported to all corners of the world. Famous models are, for example, the Boomerang 64, Faro and Presidente desk lamps.

Somewhere at the beginning of the 1970s, a series of desk lamps were designed by Fase that are, in my opinion, without a doubt copies of the Coupe series by Colombo. One of them is the Apolo desk lamp. On the shade of the Coupe lamp is a perforated line through which light shines. Even this specific detail was copied on the Apolo desk lamp. You can really see the similarity when they are next to each other.

What do you think? Do you agree that the Apolo desk lamp is a replica, or is there any room for doubt?

4.

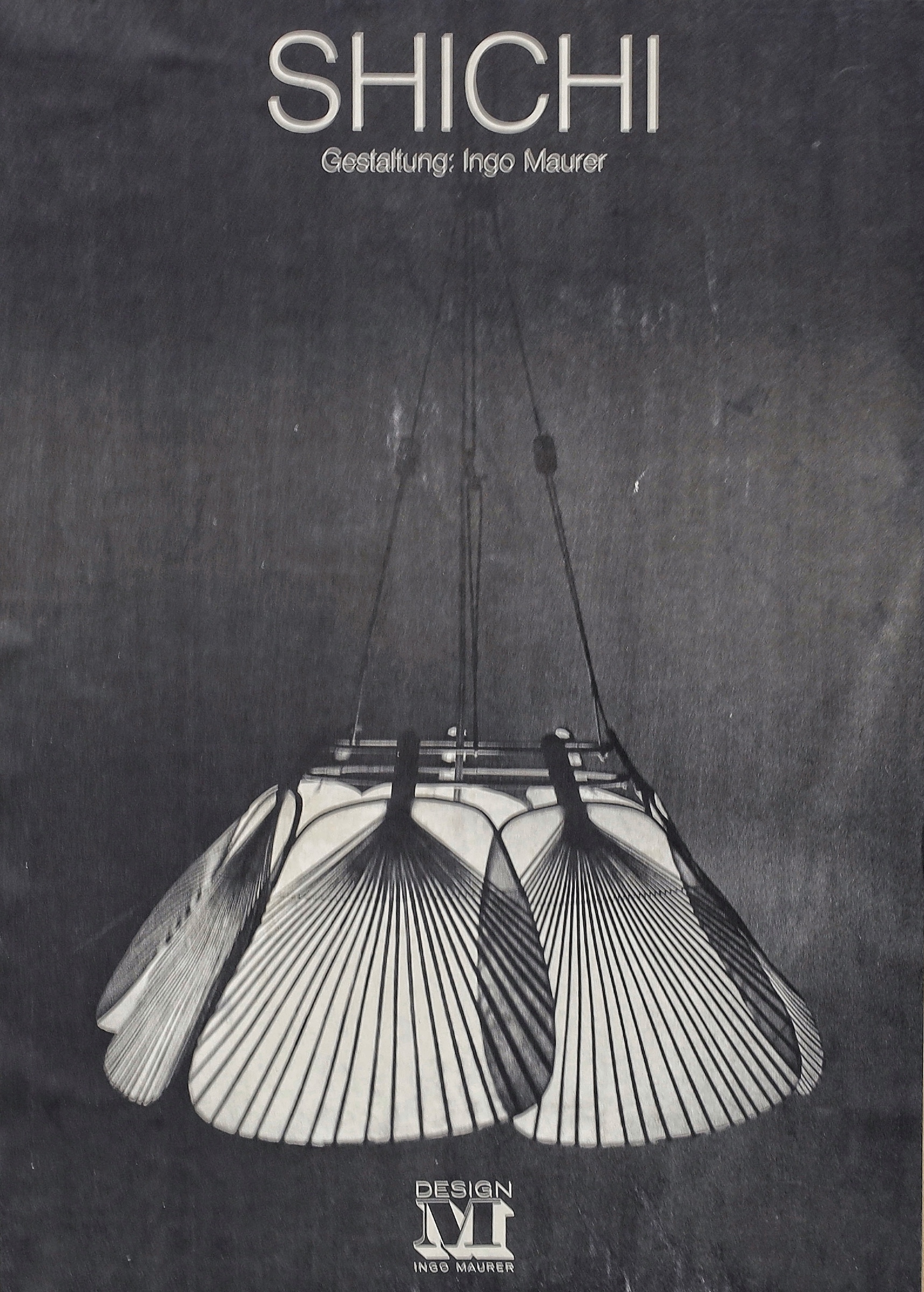

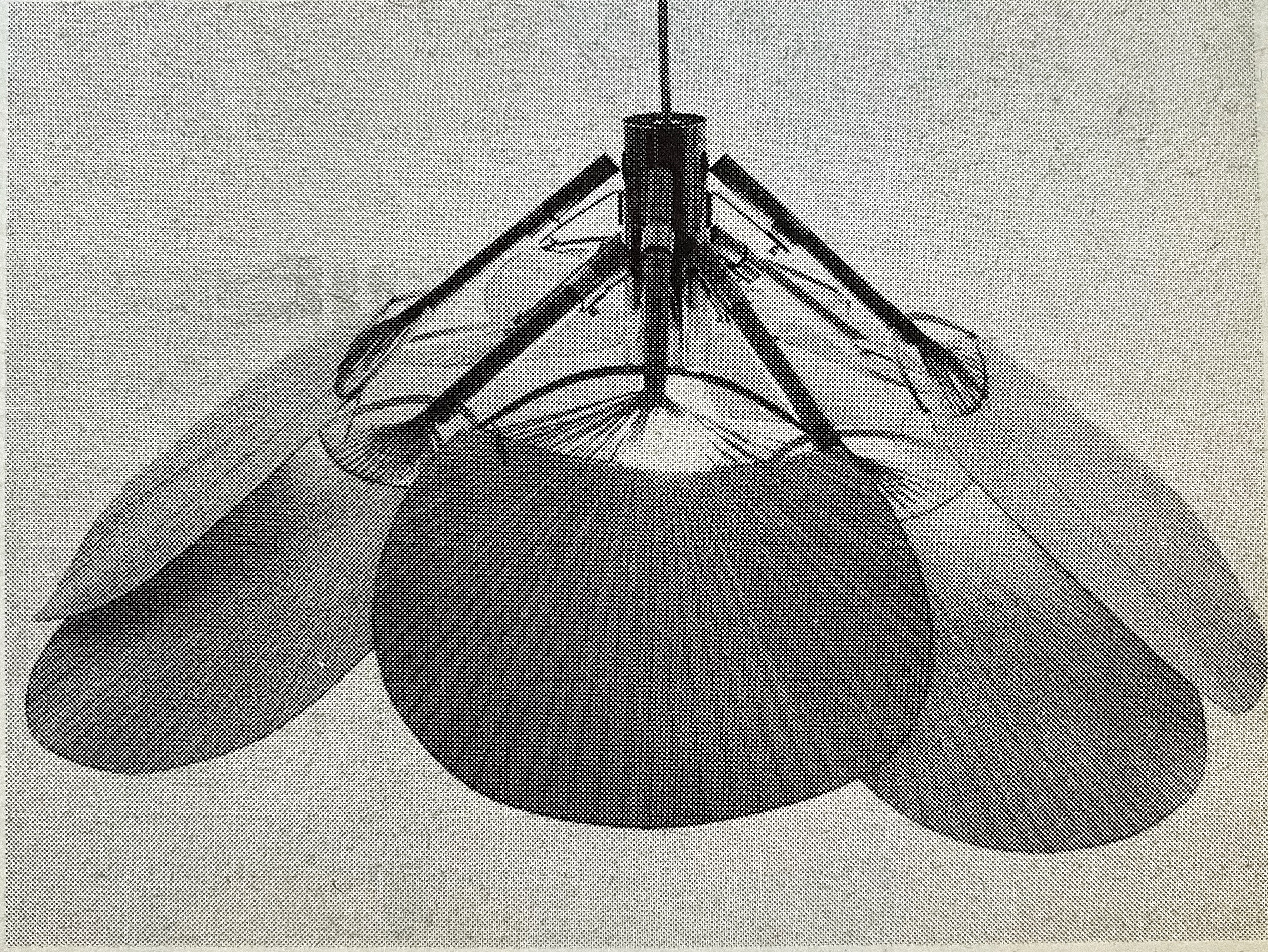

A. Shichi pendant lamp by Ingo Maurer

B. Pendant lamp by Bilumen

(7) A. Shichi pendant lamp by Ingo Maurer

(8) B. Pendant lamp by Bilumen

Ingo Maurer was a designer and manufacturer of design lighting in Germany. He designed countless lamps during the 20th century and his company is still active in the international lighting market today. Some well-known designs made by Maurer are the Bulb, Zettel’z, Lucel Lino and Ilo Ilu. In the early 1970s, Maurer was searching for a new design that would produce a very soft light. This search brought him to Paris, where he found the materials that he was looking for; bamboo and lacquered rice-paper fans. After that, in 1973, his quest brought him to Tokyo, where he sought – and found – craftsmen capable of executing the designs he had in mind.

This resulted in a collection of extraordinary lamps with shades crafted of bamboo and rice paper. The shades are made using the same techniques for making the fans that have been used in Japan for centuries. The series was named “Uchiwa”, after the Japanese word for fan. The lamps were produced in a wide variety of sizes for table, wall, pendant, and floor lamps. Some other lamps by Ingo Maurer that featured rice paper and bamboo are the Shi-Chi and Roku-Ju. The first prototypes were made in 1974.

But Maurer was not the only one who designed a lamp of this sort; I have found an advertisement featuring an almost identical hanging lamp in the Formaluce magazine from 1977. It was presented as a new lamp from the “Divisione A” series produced by the Italian lighting manufacturer Bilumen. In the advertisement, it is mentioned that Divisione A is a series of lamps unlike the usual lamps sold by Bilumen. The lamp is described as a “gilded metal hanging lamp with rice paper fans.”

One would assume at first that these lamps were made in the same factory. But in fact they are not, and I think we can say with certainty that Bilumen has copied this lamp from Ingo Maurer. Confusion because of the similarity between these designs can also be seen on the internet. The Bilumen lamp is oftentimes attributed to Ingo Maurer, for obvious reasons.

A look into Candle’s lighting catalogue

During my research I also examined a catalogue from 1973 of the Italian manufacturer Candle, which was based in Milan, Italy. They produced a wide range of vintage design lighting, mostly lamps that are nothing out of the ordinary except for a couple dozen lamps made by respected Italian designers such as Sergio Asti, Alessandro Mendini, Gio Ponti, Gae Aulenti and Mario Bellini. The most well-known table lamps produced by Candle are the Daruma, Luna, Bino and Rimorchiatore.

In this catalogue I found several lamps that are very similar to lamps created by other Italian manufacturers. They are designs that are straight-forward replicas or slightly modified in comparison to the “original” designs made before 1973. I thought it would be intriguing to take a deep dive into some of the lamps by Candle that have an uncanny resemblance to the designs of other manufacturers.

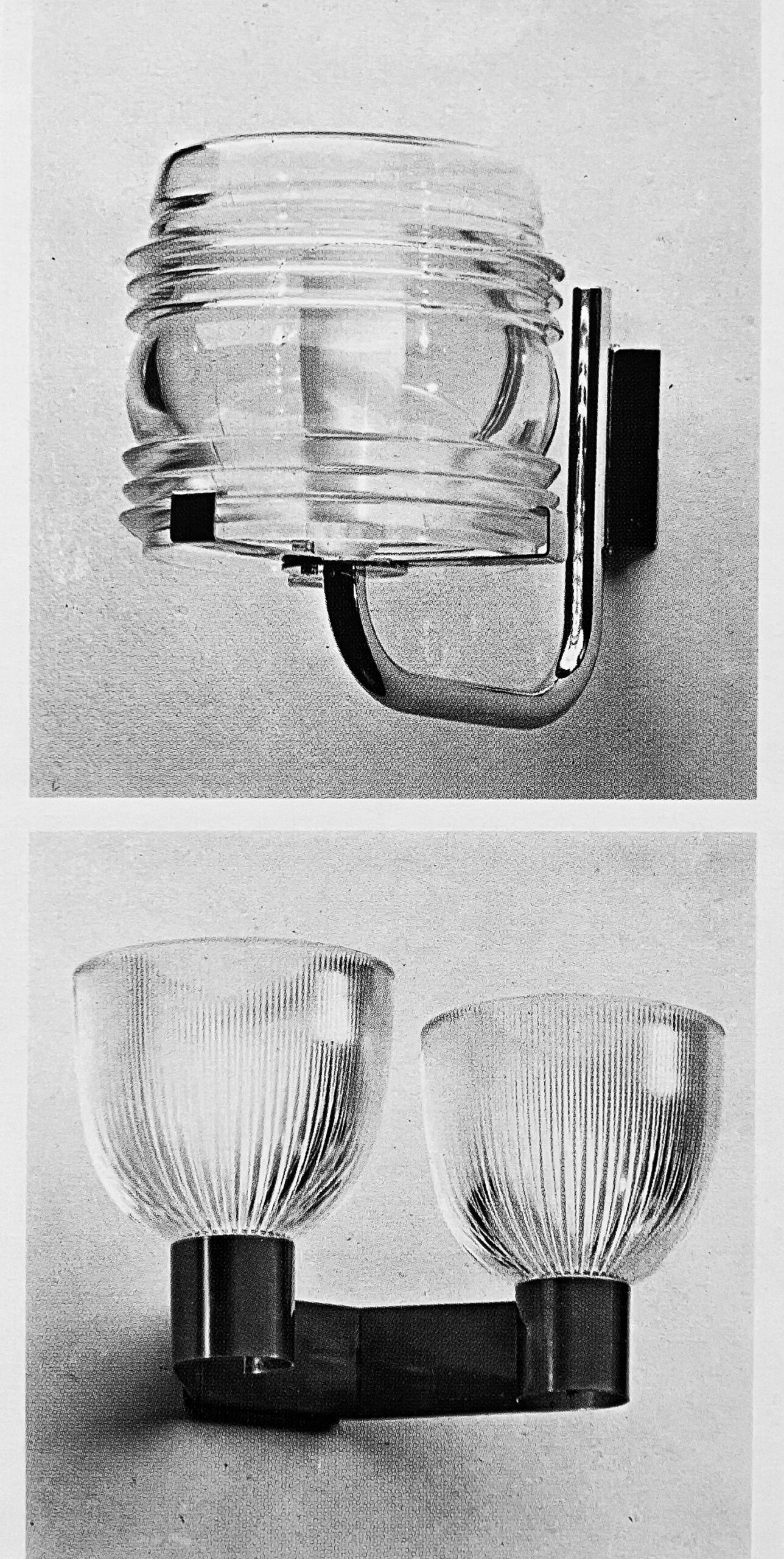

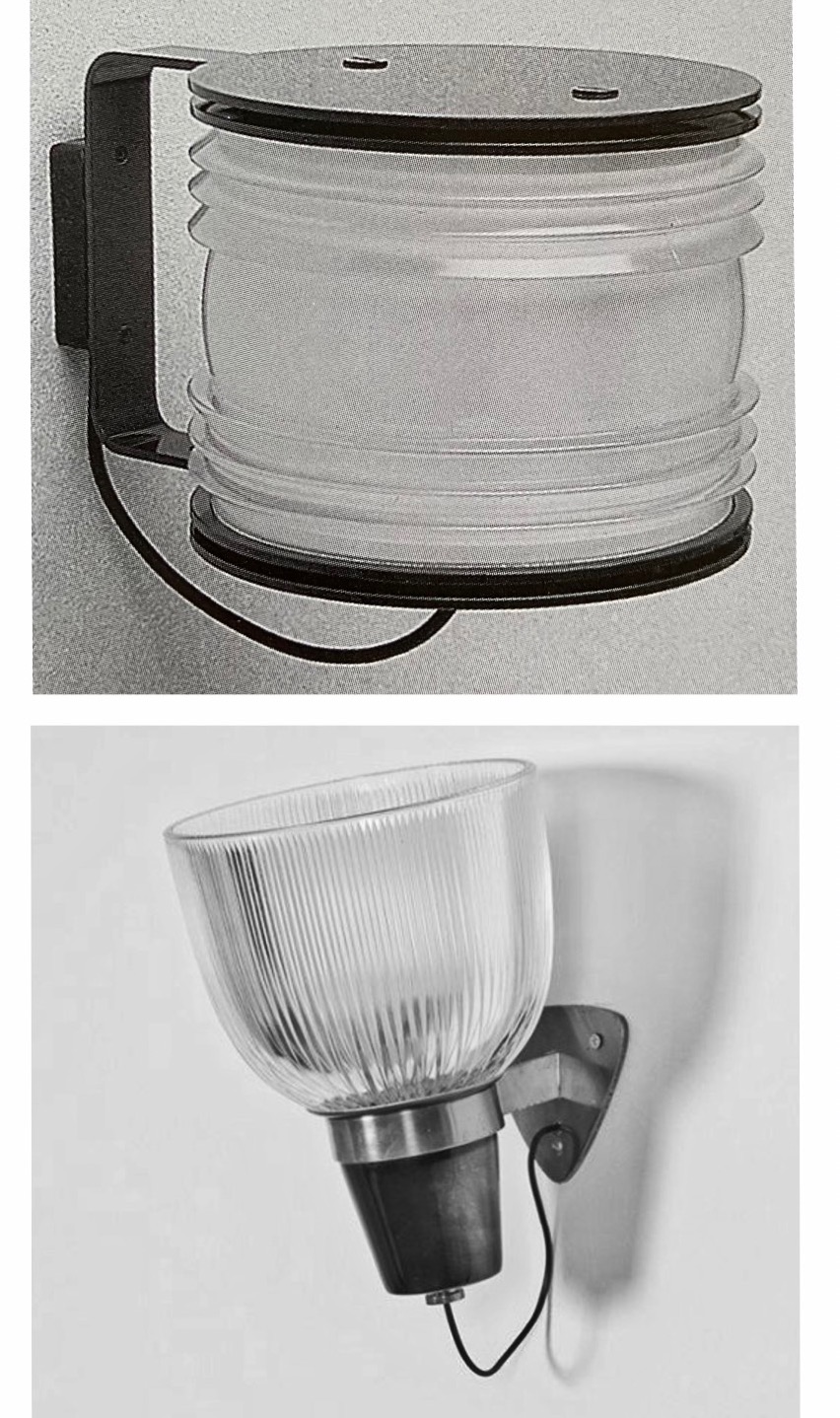

Among other things, they have made the two different wall lamps shown below that are probably inspired by designs by Ignazio Gardella and Joe Colombo. Both of these lamps are made of glass and metal. The glass parts are identical, but the structure is somewhat different.

Candle logo, lighting catalogue 1973

A.

B445 wall light by Candle, C. 1973

B448 wall light by architect E. Gozzini for Candle, C. 1973

B.

LP5 wall lamp by Ignazio Gerdella for Azucena, 1958

Fresnel wall lamp by Joe Colombo for Oluce, 1966

(9,10) A. Wall lights by Candle

(11,12) B. Top: Fresnel by Joe Colombo | Bottom: LP5 by Ignazio Gardella

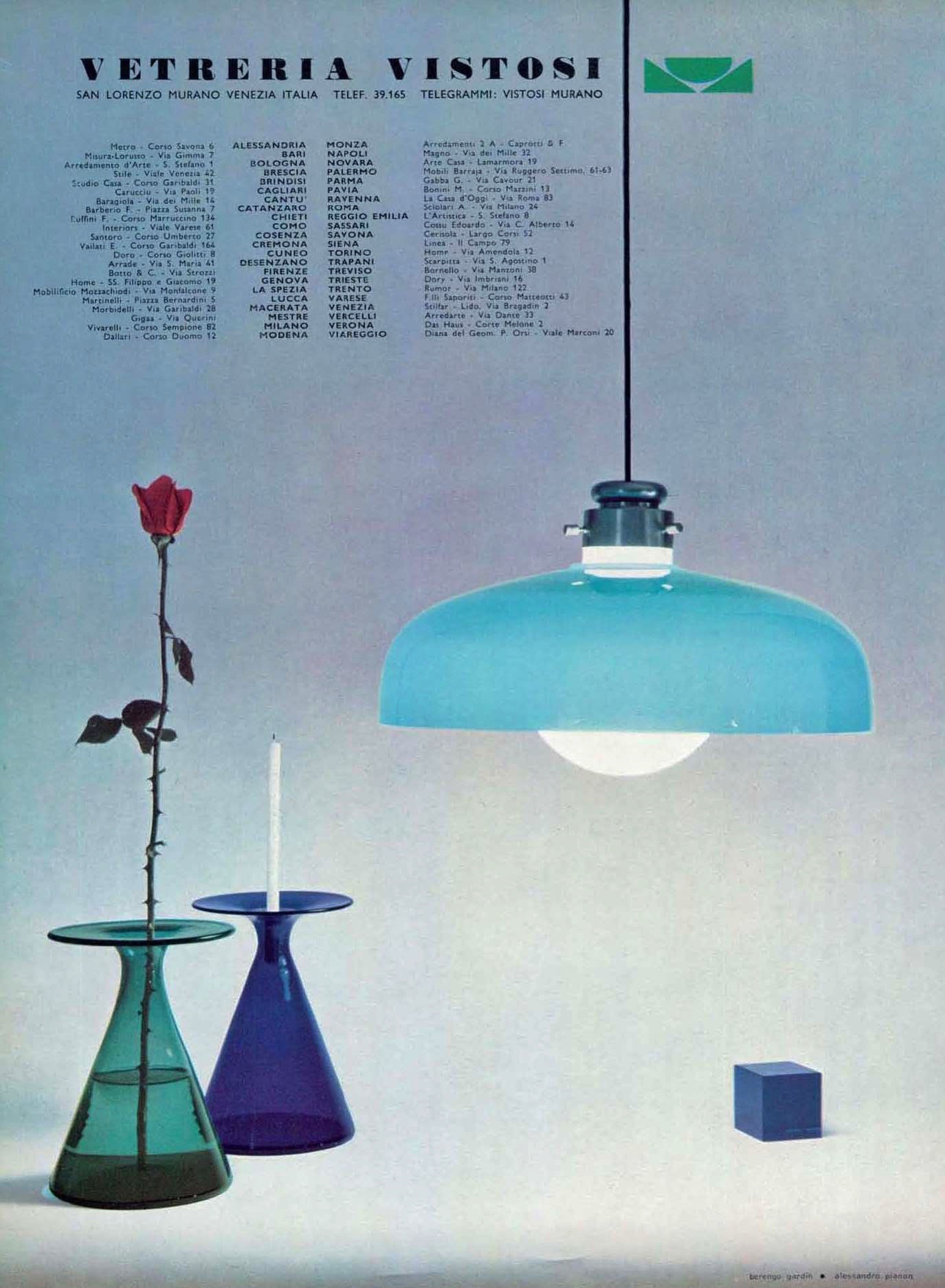

Another replica in the Candle catalogue is the A320 pendant lamp, which has the exact same shape as the pendant lamp designed by Alessandro Pianon for Vistosi in circa 1961. Unlike the Vistosi pendant, which was made of glass, the Candle lamp was made of plastic and was therefore lower in quality and much easier to produce. What strikes my interest is the fact that Pianon also worked for Candle. In the catalogue I examined, there are about a dozen lamps linked to his name. The A320 lamp in the Candle catalogue was not attributed to a designer, but there exists a possibility that Pianon was also the designer of this lamp. That would explain the obvious similarities in both designs. What is your opinion? Are the designs so similar that it has to be that Pianon designed the same lamp for two different manufacturers?

A. Pendant lamp by Alessandro Pianon for Vistosi, 1961

B. A320 pendant lamp by Candle, C. 1973

(13) A. Pendant lamp by Alessandro Pianon

(14) B. A320 pendant by Candle

A.

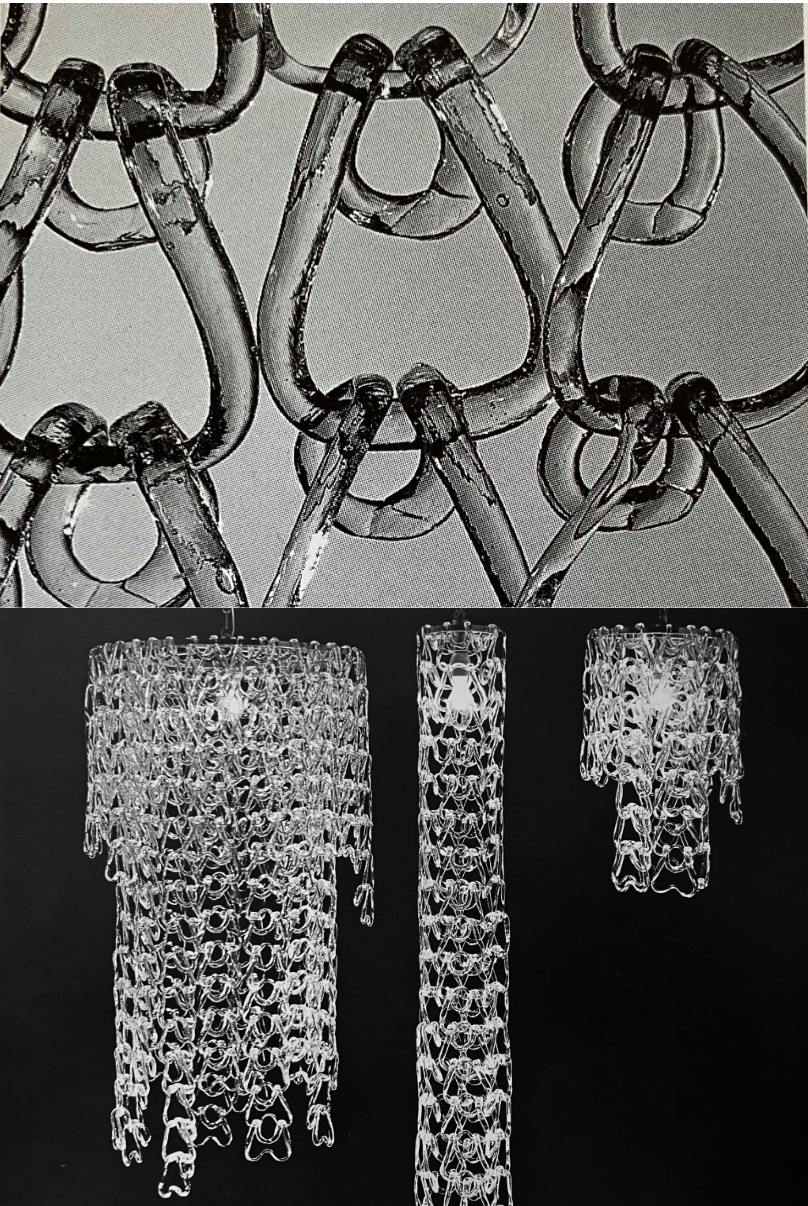

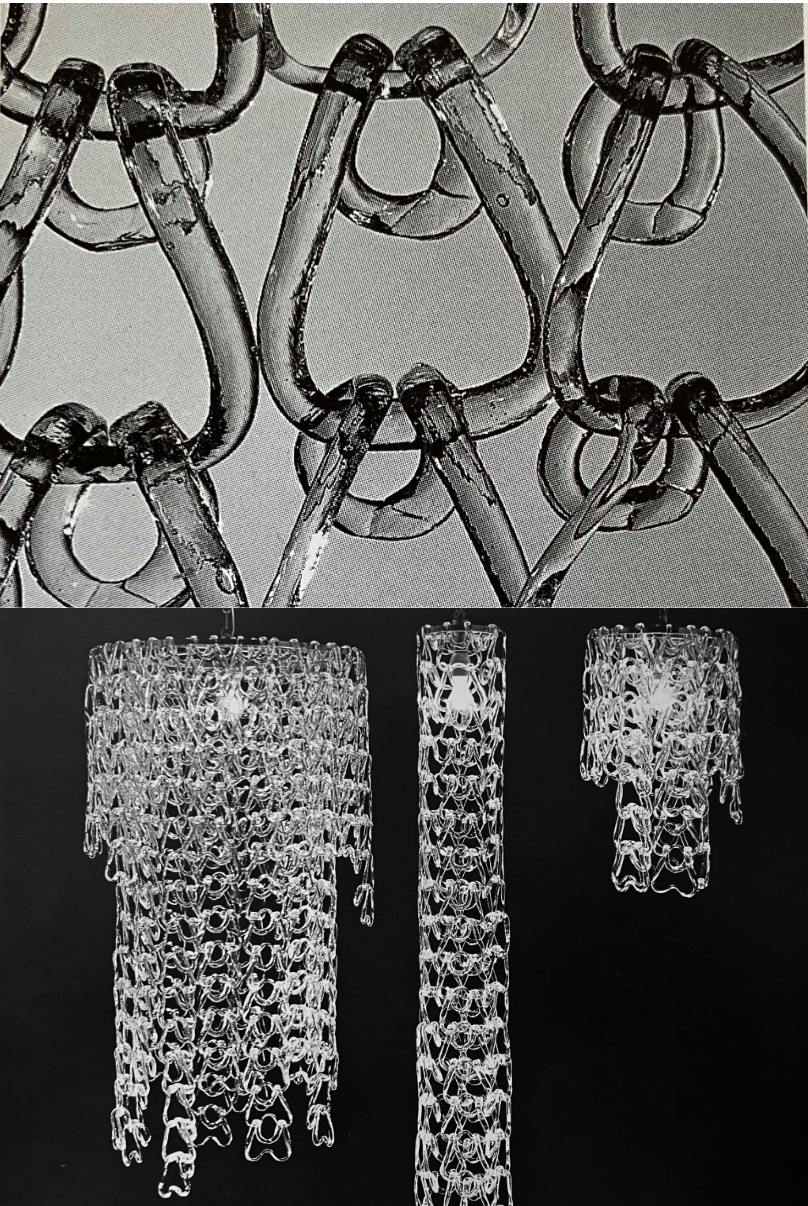

Giogali components by Angelo Mangiarotti for Vistosi, 1966

A512 – 513 – 514 chandeliers by Candle, C. 1973

B.

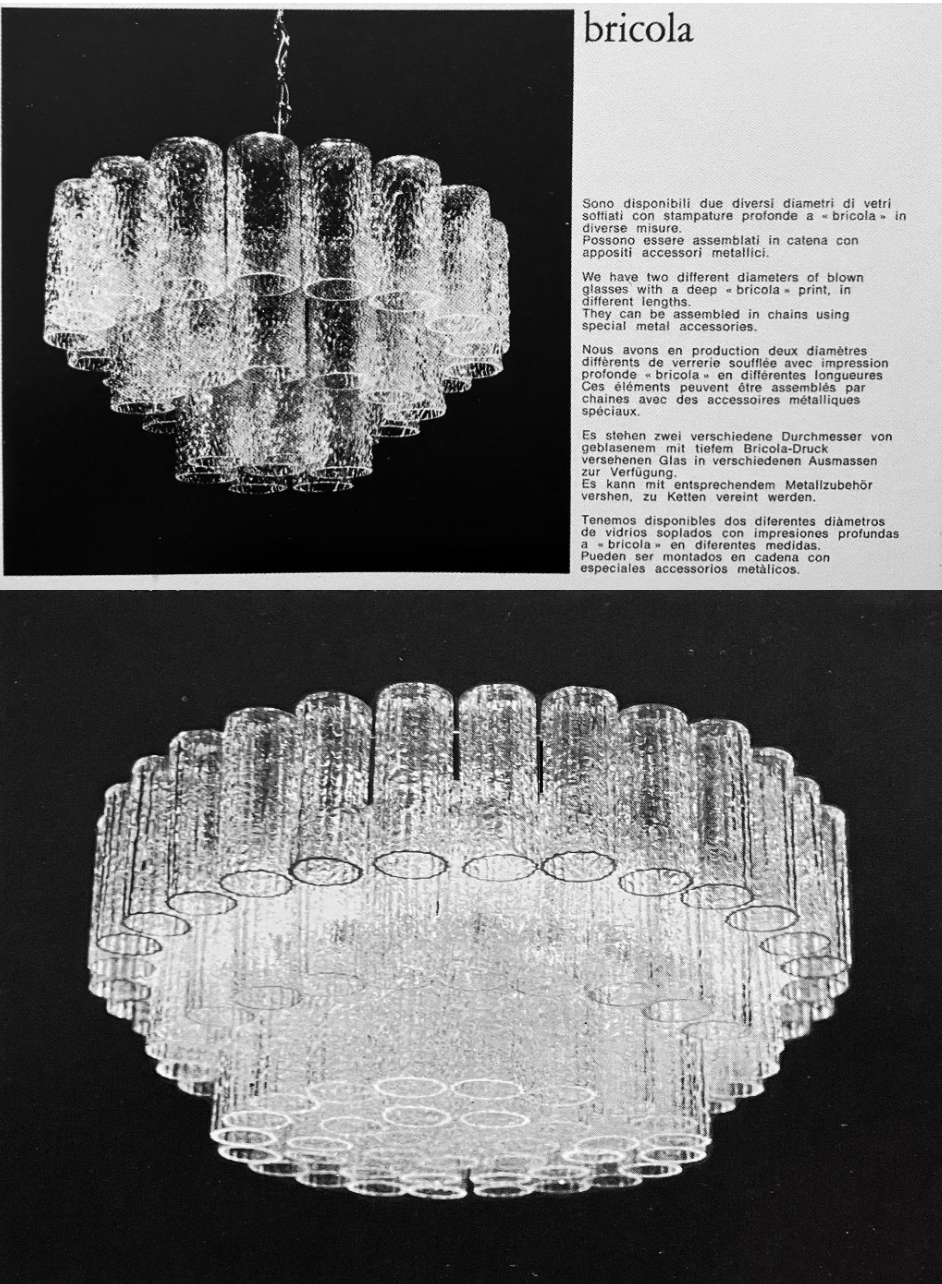

Bricola chandelier by Venini

Modular chandelier by Candle

(15,16) A. Top: Giogali components by Angelo Mangiarotti | Bottom: chandeliers by Candle

(17,18) B. Top: Bricola chandelier by Venini | Bottom: Chandelier by Candle

Candle also offered a range of glass chandeliers, which could be ordered in different sizes and shapes. They were mainly classic Italian chandeliers in transparent glass. Within their collection, two chandeliers stand out. These are copies of the Bricola chandelier by Venini and the glass Giogali components designed by Angelo Mangiarotti in 1966. The Bricola and Giogali chandeliers were designed earlier than the chandeliers featured in the Candle catalogue from 1972.

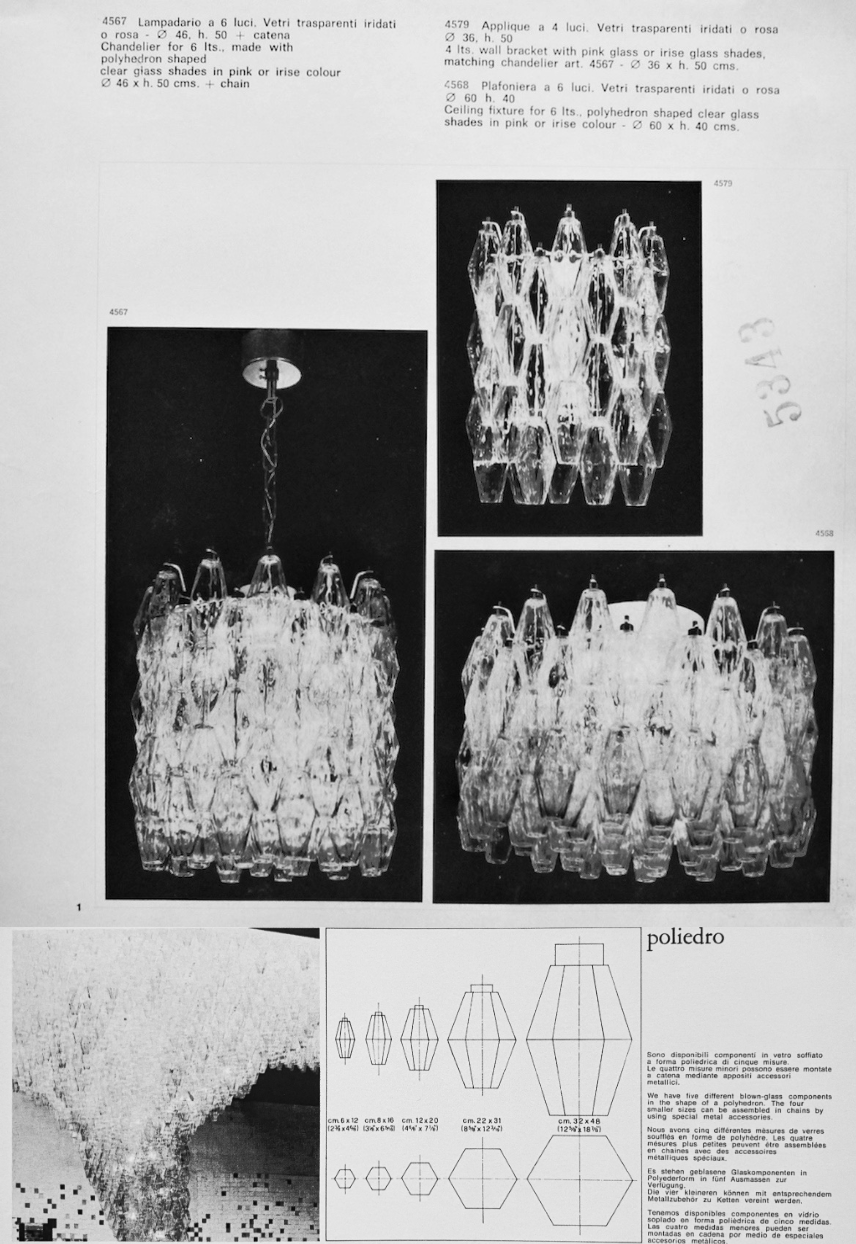

Candle was not the only Italian lighting manufacturer to copy glass chandeliers. Other small and midsize manufacturers did the same. I found another example in a catalogue from circa 1972 of the lighting manufacturer Sagim, a very small company from Mogliano near Venice, Italy, with their own glass factory. They copied the Poliedri chandelier, which consisted of diamond-shaped glass components named Poliedri. The Polierdri components were originally designed by Ignazio Gardella, Paolo Venini and Enrico Peresutti, and made by Venini in Murano. Poliedri components were first presented at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair. The Polierdi chandeliers that were produced by various manufacturers all look nearly identical, but they can be differentiated by their quality and structures. As far as we know, all chandeliers produced by Venini were distinguished from the others because they were stamped.

(19,20) Top: Chandeliers by Sagim | Bottom: Poliedro components by Venini

The Motivation for Imitation

As we have seen by the examples given in this article, lighting designers and manufacturers are often inspired by one another. Inspiration is something that makes us human. It’s part of the process of coming up with an idea and executing it. People gain inspiration in many different places and from various people. Humankind has been doing so for centuries. Without inspiration, design would not exist. It’s fine to look at each other’s work, but it becomes egregious when creators directly copy each other. What could be the motivation for Italian manufacturers and designers to imitate each other’s work?

After the explosion of new manufacturers in Italy during the beginning of the 1970s, there now existed intense competition between them. In many instances, small lighting manufacturers struggled and didn’t last longer than 5 years in existence. The bigger and more established manufacturers, like Flos, Stilnovo, Artemide and Fontana Arte, existed longer and had already built up a large network of importers throughout Europe. From a manufacturer’s perspective, it’s attractive to invest in products that you know are marketable. This could be one of the reasons why manufacturers choose to copy designs that sold well. It’s a considerable choice if a handful of copied designs made the difference between going bankrupt or staying afloat. But on the other hand, straight-forward replicating of designs is not allowed because of copyright laws, and it seems unlikely that the manufacturers of a duplicated design ever received permission from the rightful owners. Without permission, this is plagiarism, a legal offense that can be punished by a fine. In the case of plagiarism the creator of the original also has the right to file claims for damages. It’s unclear if any rightful owners ever gave permission or filed claims in the examples given in this article.

It could also be that the creators of the original lamps didn’t know or didn’t care that their design was being copied. After all, we are talking about a very small percentage of the total production of Italian lighting during the second half of the 20th century.

Some of the designs shown in this article can get the benefit of the doubt. In the end, it could all be coincidence, but in my opinion there certainly are connections between some of the aforementioned lamps.

Conclusion

In conclusion, lighting manufacturers and designers looked at each other’s ideas for inspiration. For some, it was really just inspiration; for others, an original idea was seen as an invitation to exactly duplicate a design. Various Italian manufacturers made identical lamps to those made by other designers and presented them as their own.

Italian vintage design lighting is a lot broader than most people think. There were hundreds of Italian manufacturers that made lamps in similar styles; some are yet to be discovered. When looking for a unique lamp, search for something unknown that was less successful during its period, but always try to find a reference and check the details to prevent an unsatisfactory purchase. Search for references to old magazines, books, or archives, but never rely on the information that is scattered around on the internet.

All content is sourced and generated internally.

Text: Storm Wilschut, Zara van Hoof

Copyright: This article and its contents may not be used or copied without permission of Storm Vintage.

Sources:

Vintageinfo.be

Venini.com

Fasethebook.com

Nytimes.com

Published: 27 June 2023

References and image sources:

- Moonlight floor lamp by Ettore Sottsass for Arredoluce

Formaluce N.37 1973 November – December, page 42

Image source 2: Lamps 1968-1973 New Italian Design, Fulvio Ferrari - Art. 225/1 by Bosi, Martini and Bertotti for Fratelli Martini

Formaluce N.46 1975 May – June, page 3 - Pausania desk lamp by Ettore Sottsass for Artemide, 1982

Repertorio dell’arredo domestico 1950-2000, Giuliana Graminga, page 310 - 6770 desk lamp by Robert Sonneman for George Kovacs

The Lighting Book: A Buyer’s Guide to Locating Almost Every Kind of Lighting Device, Martin Greif, page 139 - Coupe desk lamp by Joe Colombo for Oluce, 1967

Repertorio dell’arredo domestico 1950-2000, Giuliana Graminga, page 141

Image source: Buskowskis - Apolo desk lamp by Fase Madrid

Fase Madrid, Catalogue 1974

Image provided by Vintageinfo.be - Uchiwa pendant by Ingo Maurer

B. Dessecker, F. Koschembar, K. Wengmann, Ingo Maurer: Designing With Light, page 72

Image source: sticker from original packaging - Bilumen pendant lamp

Formaluce N.62-63 1977 January – April, page 85 - B445 wall light by Candle, C. 1973

Candle catalogue: Illuminiazione per l’arradamento, 1973, page 115 - B448 wall light by architect E. Gozzini for Candle, C. 1973

Candle catalogue: Illuminiazione per l’arradamento, 1973, page 115 - Fresnel wall lamp by Joe Colombo for Oluce, 1966

Repertorio dell’arredo domestico 1950-2000, Giuliana Graminga, page 131

Image source: Repertorio dell’arredo domestico 1950-2000 - LP5 wall lamp by Ignazio Gerdella for Azucena, 1958

Repertorio dell’arredo domestico 1950-2000, Giuliana Graminga, page 38 - Pendant lamp by Alessandro Pianon for Vistosi, 1961

Domus N. 381, August 1961, page 8

Image source: Domus N. 386, January 1962, page 102 - A320 pendant lamp by Candle, C. 1973

Candle catalogue: Illuminiazione per l’arradamento, 1973, Page 39 - Giogali components by Angelo Mangiarotti for Vistosi, 1966

Repertorio dell’arredo domestico 1950-2000, Giuliana Graminga, page 131 - A512-13-14 chandeliers by Candle, C. 1973

Candle catalogue: Illuminiazione per l’arradamento, 1973, Page 67 - Bricola chandelier by Venini

Venini Luce 1921-1985, Le Stanze Del Vetro, Skira, page 612 (catalogue from 1975) - Modular glass chandelier by Candle, C. 1973

Candle catalogue: Illuminiazione per l’arradamento, 1973, Page 56 - Model 4567-79-68 chandeliers made by Sagim

Sagim red catalogue C. 1973, page 1 - Poliedri components by Ignazio Gardella, Paolo Venini and Enrico Peresutti for Venini, 1958

Venini Luce 1921-1985, Le Stanze Del Vetro, Skira, page 612 (catalogue from 1975)